February 10, 2026

by Daniel Vesecky

Click here to download an executive summary of the report

Click here for a one-pager on Chicaago's budget process

Click here to read President Joe Ferguson's op-ed in Crain's Chicago Business

Legislative deliberations over the City of Chicago's (Chicago or ‘the City’) FY2026 budget, which ran from mid-October through passage in late December 2025, were a contentious, opaque, and at times messy affair that laid bare what has long been a deeply flawed process. In the absence of formal structures, procedural rigor, sufficient technical resources and expertise, and standards-based decision-making, the process devolved into confusion that at times verged on chaos, prompting not unreasonable concerns about a possible government shutdown.

This dysfunction was borne of a simple fact: a massive imbalance of power between the executive (Mayor) and legislative (City Council) branches of Chicago’s government. The City’s current budget process is designed for City Council to rubber-stamp the Mayor’s budget. If the Council does not pursue significant changes to the Mayor’s proposal, the system works as intended: timely passage of a technically, if not always structurally, balanced budget. That low bar has led to short-sighted and poor financial decision-making, resulting in recurring structural deficits and mounting debts.

The moment City Council seeks to exercise its legislative duty to be a fiduciary check on Chicago’s executive branch, the customary process falls apart. This is precisely what we saw play out in the most recent budget cycle. What ensued was a deeply chaotic, mistrustful, and confusing season of conflict between the Mayor and the City Council that produced a final budget that made only marginal improvements to the Mayor’s deeply flawed proposal, but still fell far short of a budget that a fiscally fragile Chicago needs. Key reasons for that outcome included disproportionate Mayoral control of information and process and a clear lack of budgeting and analytical capacity within the City Council itself.

If Council members intend in the coming years to continue to exercise their responsibility to scrutinize and, where necessary, revise the Mayor’s proposed budget—which we emphatically hope they do—their effectiveness will hinge on building a new budget process that balances power and improves critical engagement between Chicago’s City Council and Mayor’s Office.

The City Council could enact a few key reforms to strengthen its hand in the following aspects of the budget process:

1. Control of Information and Leadership

- Guarantee City Council access to financial information: Legislate by ordinance, City Council's entitlement to all information and analysis from the executive branch, including the Budget Office, Office of the Chief Financial Officer, and Comptroller. Include a corresponding mandatory duty to cooperate in all matters and hearings occurring before the Council and its committees.

- Establish independent Council leadership: Select a leader from among alders to represent City Council outside of full Council meetings, over which, by state law, the Mayor presides.

- This leader would identify a chief budgeteer and a budget negotiating team.

- The leader would also nominate committee chairs, replacing the conflict-laden prevailing norm of Mayoral appointment of the chairs of legislative committees whose core responsibility is legislative oversight of operations under the Mayor.

2. Strengthen Legislative Resources:

- Expand and professionalize the City Council Office of Financial Analysis: Empower an independent legislative budget office (currently an under-resourced Council Office of Financial Analysis) by increasing its budget, staffing, and analysis capacities, while ensuring the staff is fully professionalized and has subject matter expertise aligned with the needs of the City Council.

- Create permanent, professional committee staff: Professionalize and make permanent committee staff through hiring standards and guidelines that focus on the skills and expertise needed to support each subject matter area and serve the Council as a whole.

- Limit committee staff to legislative work only: Institute requirements that committee staff do only committee work. This would end a customary practice (in extreme tension with state and local laws) of committee staff working on ward-level constituent services or other tasks benefiting the chair of that committee.

3. Improve the Budget Timeline:

- Move the timeline up: Move the budget release to earlier in the year to allow for meaningful review. Also, move the timeline of mid-year reports and mid-year budget hearings earlier in the year, so that they can better establish the foundation needed for assessment of current fiscal year challenges to inform the next budget cycle.

- Require a formal Council response: Create within the timeline a mandatory formal response from Council to the Mayor’s proposal, outlining amendments and possible alternatives to the Mayor’s plan, to which the Mayor must respond.

The analysis below revisits the FY2026 cycle to identify where the process broke down and how those failures point directly to the reforms outlined above.

Breakdowns in the FY2026 Budget Cycle

To get to the key changes the City of Chicago should make to its budget process, let’s first revisit how this most recent budget process played out and where and why things broke down.

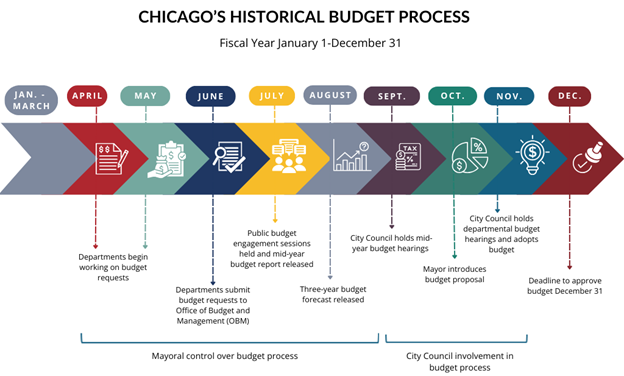

The formulation of the budget by the Mayor’s financial team begins in the spring, but the City Council’s official engagement does not begin until the Mayor formally introduces a proposed budget, typically between late September and late October, accompanied by a budget address to the full City Council. This budget generally consists of four components that must be passed by the Council: a revenue ordinance, an appropriations ordinance, a debt authorization ordinance, and a management ordinance, which outlines the rules for the budget’s implementation. In 2025, the Mayor introduced the proposed FY2026 budget in Mid-October, which is the norm. The City’s fiscal year runs from January 1 to December 31, in line with the calendar year, and a balanced budget must be adopted by the end of December.

The Mayor’s FY2026 budget proposal was structurally imbalanced and employed several highly controversial measures to close a $1.2 billion deficit. Some of the most controversial decisions included:

- A “head tax” of $21 per employee on Chicago employers with over 100 employees, projected to raise $100 million in revenue.

- Reducing the City’s advance pension payment by nearly half, cutting pension expenditures by $118 million in FY2026, but costing the City more in future years. The Mayor’s team had previously characterized this as a necessary payment to avoid a credit rating downgrade.

- A proposal to issue approximately $450 million in short-term debt to cover operating costs—specifically, retroactive backpay for firefighters under a newly negotiated collective bargaining agreement and costs associated with judgments and settlements arising from police misconduct claims.

- Declaring a record high $1 billion Tax Increment Financing (TIF) surplus, of which the City would retain approximately $233 million. This level of surplus sweep would drain the funds held in many TIF districts and potentially reduce available funding for future economic development projects.

- Requesting a massive $1.8 billion debt authorization for infrastructure and refinancing without careful consideration by the City Council.

- Implementing only a small percentage of the hundreds of millions of dollars in potential savings and efficiencies identified by a Mayor-appointed task force and by a separate and parallel consulting report, both commissioned by the Mayor’s Office in advance of the budget.

The budget proposal broke from best practices and the City’s own recent efforts to move away from risky financial practices. In particular, it included issuing debt to cover the cost of legal settlements (a practice that was phased out during the Emanuel administration). It also departed from the policy of increasing pension contributions through advance payments above the statutory minimum to slow the growth of unfunded pension liabilities (first implemented in 2023 under the Lightfoot administration).

Municipal market evaluators also flagged concerns about the budget. In early November, credit rating agency S&P Global changed Chicago’s credit outlook from neutral to negative, signaling a potential downgrade. S&P identified as particularly troubling the proposed budget’s intention to reduce the advance pension payment, pay operating expenses with new debt, and largely ignore efficiencies. Soon after, the City issued new bonds to refinance existing debt. However, the underwriter had to take down $75 million from a fully securitized offering even though it offered comparatively high interest returns for participating lenders: another red flag. Taken together, these signals suggested that the market was already internalizing the expectation of a downgrade, possibly even into junk territory, which the City is only two notches above.

Immediately after the release of the budget proposal, the Mayor’s Office also released a report by consultants from EY (formerly known as Ernst & Young), which the Mayor’s Office had commissioned and paid for. The report detailed potential savings and efficiencies the City could implement to streamline its budget, many of which required little to no reduction in service provision or staffing. The report estimated that Chicago could save between $530 million and $1.4 billion over the next decade if its recommendations were implemented. Despite commissioning this report, the Mayor’s budget proposal contained only a handful of small pieces of the EY report’s recommendations, leaving hundreds of millions of potential savings on the table.

Following the introduction of the budget, the City Council instantly broke from its longtime customary practice of generally falling into line with the Mayor’s proposed budget. Historically, the final budget passed by the City Council has typically involved only minor changes to the Mayor’s proposal. This time, a majority of the City Council rejected the Mayor’s revenue proposal, primarily centered on opposition to the head tax. On November 17, 2025, the City Council’s Finance Committee voted 25–10 to reject the revenue component of the budget.

Throughout November and early December, alders pursued alternative proposals to increase revenue and reduce spending to close the $1.2 billion budget gap without the Mayor’s proposed head tax or pension advance payment reduction. They sought direct public testimony from the City’s Office of Budget and Management (OBM), the Department of Finance, and the EY consultants who crafted the report on efficiencies. However, all sources of budget information, analysis, and testimony were controlled by the Mayor’s Office, which minimized disclosure of information needed by Council to craft responsible budget alternatives.

With insufficient internal resources to fully develop an alternative to the Mayor’s budget proposal, multiple informal groups of budgeteer alders sought help from various outside stakeholders. The lead cohort (in which the Civic Federation played a supporting role) included civic organizations, former City officials with finance and budget expertise, political and communications professionals, and representatives of both the business and labor communities.

After weeks of closed-door negotiations within the Council, in December alders produced an alternative budget that largely tracked with the Mayor’s proposal but made a few significant changes, including eliminating the proposed head tax and making the full advance pension payment. The alternative proposal retained the short-term borrowing and the record TIF surplus from the Mayor's budget proposal. To balance these changes, the alternative budget increased the personal property lease tax (PPLT or ‘cloud tax’) to 15%, required the City to find an additional $47 million in efficiencies, and required the City to sell uncollected City debt for $92 million. In addition, Council members proposed a variety of other revenue sources, including legalizing video gambling, advertising on more City property, licensing City buildings for alternate reality advertising, and raising the City’s shopping bag tax.

On December 20, 2025, the Council passed the alternative budget in a 30-18 vote. Mayor Johnson chose not to veto or sign the budget, an unusual response meant the budget automatically took effect on January 1, 2026, without any action by the Mayor.

Ultimately, the alternative budget improved on the initial proposal by prioritizing reducing the City’s pension burdens and eliminating the head tax. However, the final budget did not eliminate the highly concerning decision to issue debt to pay for operating costs, nor did it address the City’s structural deficit problem. The final budget leaves Chicago facing a similarly enormous deficit in FY2027 and in no better position to handle closing that budget gap. Once again, we saw a piecemeal approach to budget balancing that avoided long-overdue streamlining and restructuring of operations and relied on one-time revenues and small tax and fee increases over long-term sustainable solutions.

Structural Failures Exposed in FY2026

The FY2026 budget cycle did not break down simply because of disagreement—it broke down because the existing budget process doesn’t provide the framework for a decision-making process that allows for meaningful Council oversight and negotiation. The failures below are grouped into three areas: information and leadership, resources, and timeline.

Control of Information and Leadership

The FY2026 budget cycle exposed longstanding structural issues in how budget information is controlled. The Mayor’s Office maintains near-total authority over all financial data, analysis, and expert resources. The City Council, while legally responsible for approving a balanced budget under State law, lacks both the authority and the tools to independently obtain or verify this information. This chokehold on information makes meaningful legislative oversight and engagement of the Mayor’s proposal extremely difficult, if not impossible.

During the budget hearings, department heads defended their budgets in response to questions from alderpersons. These hearings were held this year from October 21 to November 6, a customary practice that is too soon after introduction for alders to fully prepare. Requests for additional information “through the chair” were frequently delayed, sometimes arriving far too late to be useful. From the outset, Council members faced a serious information deficit, a dynamic that persisted through the end of the year.

A particularly notable example involved the EY consultant report on efficiencies and savings. The Council requested access to the underlying data and analysis but could not compel it, as alderpersons lack subpoena power for third-party testimony and the Administration is not legally required to provide the information. A hearing was eventually held with EY representatives, but the Mayor’s budget and finance directors monopolized the discussion, leaving many of the alders’ questions insufficiently answered. Consequently, alderpersons could not determine which recommendations could be implemented quickly or quantify potential savings. This left the Administration with almost total discretion over which efficiencies would be pursued and how savings would be implemented.

Other examples of restricted information included:

- Refusal by the Mayor’s Office to disclose details supporting implemented efficiencies or calculations behind the projected savings.

- Opaque methods underlying the estimated $100 million in head tax revenue and subsequent revisions.

- Limited ability for alderpersons to evaluate the merits or feasibility of proposed alternatives.

- Testimony from executive branch members restricted to the budget committee.

This lack of transparency hampered independent analysis and constrained the Council’s ability to craft a fully informed alternative budget. Alders attempting to propose alternatives had to rely on external experts, and even then, their work was constrained by limited access to the Administration’s data.

Leadership Structure

Chicago’s 50-member City Council is very large. Combined with a large committee structure, this makes for unwieldy budget negotiations. Setting aside issues of size and committee organization, the Council faces a deeper structural problem: it has no formal leadership framework beyond the Mayor. The Mayor serves as the presiding officer and appoints all committee chairs. The Council lacks a first-among-equals, speaker-like leader who can set the rules and processes for City Council Committees and ensure centralized representation in budget negotiations.

Although alderpersons were able to hold together a majority of 26+ members against the proposed budget, they spanned the ideological spectrum and often opposed the proposal on differing grounds—some focused on rejecting the head tax, while others focused on opposing short-term borrowing. Without a clear leadership structure, internal communication was fragmented, with outside stakeholder groups providing supporting staffing and expertise to effectively shape priorities and the agenda. The budget committee, the natural venue for such negotiations, was controlled by a loyal mayoral appointee and therefore could not serve as an organizing center for the alternative budgeteer caucus. While some alderpersons emerged organically as leaders, the opposition had no single individual with ultimate voice or actual authority.

Interactions with the Mayor were similarly complicated. Budget stances were expressed publicly through the media, with the Mayor threatening vetoes on some proposals and tacitly accepting others, while the alternative budgeteers gradually built toward a veto-proof majority. The combination of a large Council, fragmented opposition, and informal negotiations meant it was unclear until the final days which alternative budget the Council would ultimately propose and pass.

These dynamics demonstrate the critical need for formal leadership and negotiation structures within the City Council. Establishing a recognized internal leadership role, empowering a team of alderpersons to coordinate budget strategy, and creating a more functional committee system would allow the Council to communicate more effectively.

Legislative Resources

Beyond the challenges of information access, Council members lack sufficient internal resources to analyze and respond to the Mayor’s budget. The Council Office of Financial Analysis (COFA) provides technical analysis, but its four-person staff is far below what is needed to analyze all aspects of a $17 billion city budget. Individual alderpersons’ ward staff are largely dedicated to constituent services, leaving little capacity to support budget work.

Committee staff, such as those in the Finance or Budget Committees, are controlled by committee chairs—who are appointed by the Mayor—and are often assigned non-budget tasks. While the Finance Committee Chair broke with the Mayor to support the alternative budget, such occurrences are unusual.

Historically, limited staffing and analytical capacity have disincentivized alderpersons from challenging the Mayor’s proposals. In the FY2026 cycle, the Council’s lack of internal resources contributed to a drawn-out, uneven process: alderpersons did not work from a complete, shared set of facts, resulting in conflict and delays. Better staffing and access to independent analysis would allow the Council to craft and pass a budget that more effectively addresses the city’s fiscal challenges.

Compressed Budget Timeline

With the Mayor’s proposed budget released in mid-October and the statutory deadline for passing a balanced budget by the end of December, the City Council has only two and a half months to analyze the budget proposal, hear from stakeholders, consult the public, debate alternatives, negotiate amongst themselves, and pass a final budget. In past years, all of this occurred in a matter of six weeks before Thanksgiving. Even if City Council had ample staff, strong budgeting expertise, and full access to City information, that window would still be too short for serious review. The Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays further reduce the available window of time.

The compressed budget timeline is also compounded by a flawed process structure. Once the Council receives the Mayor’s budget proposal, department hearings begin immediately, leaving alderpersons too little time to examine the budget in depth. The process does not require City Council to prepare amendments or publicly propose alternatives at any stage, nor does it require the Mayor to respond to proposals. In the fall of 2025, we saw these gaps produce a chaotic process where intense negotiations stretched into late December, and alders unveiled and voted on an alternative budget just days before the final deadline.

The Council also does little work to prepare in advance of the budget release, although this has started to change over the past year following the passage of new requirements to the Management Ordinance intended to improve early oversight, transparency, and Council access to budget information. These included new mid-year budget reports from OBM and COFA, accompanied by mid-year budget hearings. While City Council commissioned the mid-year reports and held the mid-year budget hearings, those hearings were held in September, too far past the mid-year point and too close to the budget introduction to be useful in preparing for the 2026 budget. These additional reporting mechanisms were a positive first step, but scheduling them earlier in the year would increase their practical impact.

New York City: A Model for How Chicago Can Improve

No American city has a perfect budgeting process or a perfect budget. But as we seek to move Chicago’s City Council closer to the goal of being a co-equal check on the power of the executive branch, New York City (NYC) stands out as a key example to model. The NYC budget process allows its City Council to have robust input into the budget while still enabling collaboration between the City’s Mayor and Council. Chicago could borrow from many aspects of NYC’s budget process.

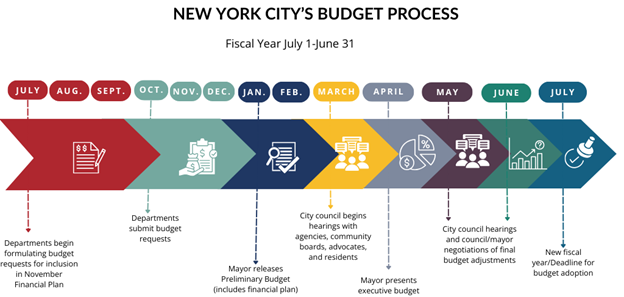

New York City’s nearly eleven-month budget process is much longer than Chicago’s, beginning in August and lasting through the end of June. Departments submit their budget requests in late August, and the budget office has four months to draft the proposed budget. Once the budget is released, the New York City Council has five months to review and pass the city’s budget, which provides time to more thoroughly review departmental requests.

In January, the New York Mayor releases a preliminary budget that outlines goals and funding allocations for the coming fiscal year. This includes a financial plan covering economic and revenue forecasts, five-year agency summaries, and other information; a summary of savings initiatives implemented across city agencies; departmental estimates; and other information. From March to April, the City Council analyzes the preliminary budget and convenes a series of hearings with city agencies, community boards, advocates, and residents. At the conclusion of the hearings, the city council is required to issue a formal response to the Mayor’s preliminary budget that includes suggested revisions and provides updated financial data. This essentially serves as the City Council’s version of the proposed budget.

Following consideration of these revisions, the Mayor presents the executive budget in April. Upon release, the City Council conducts another analysis and holds a second series of hearings, with the Council and Mayor negotiating the final adjustments before adopting a budget by the start of the new fiscal year on July 1. The City Council’s elected president creates a smaller negotiating team of council members, who interface directly with the Mayor to facilitate negotiations.

New York City also has several government bodies that conduct analyses to provide multiple independent viewpoints. NYC’s primary source of independent analysis comes from the city’s Independent Budget Office (IBO), which has a robust research presence with over 40 staff members, multiple analytical reports about the annual budget, and regularly updated guides to the budget process aimed at the general public. In addition to the IBO, New York City has an independently elected City Comptroller who provides commentary on the city’s proposed and adopted budgets each year. The State Comptroller’s Office also has a specialized team dedicated to analysis for New York City. The State Financial Control Board provides yet another layer of independent financial oversight for the city. This means that members of New York City’s City Council have many different sources of information and research to turn to that are independent of the Mayor’s Office when evaluating the proposed budget.

A few aspects of NYC’s system stand out as clear improvements that Chicago should consider adopting. In particular, the New York City Council:

- Is supported by a well-staffed independent budget office.

- Has five months to review and approve the Mayor’s budget, compared to Chicago’s two and a half months.

- Has a formal process mandating a Council-generated alternative proposal to the Mayor’s budget.

- Chooses committee chairs and elects a Council Speaker, who plays a central role in assigning committee chairs and leadership teams.

- Has the power to compel testimony and information sharing from the executive branch.

A notable difference between the two cities is that New York’s budget process described above is written into a municipal charter. Chicago currently does not have such a governing document through which many of these process changes could be enacted and enforced.

In comparison to New York City, Chicago’s budget process does not have robust opportunities for the City Council to weigh in. NYC spends the entire year preparing its budget, whereas Chicago does not even begin at the department level until April. The City Council is really only involved in the budget process for up to three months of the year—and in reality, closer to six weeks. In contrast, New York provides their Council with five months to debate the Mayor’s proposed budget and present a budget alternative. Chicago has no such requirements or processes.

How Chicago Can Reform the Budget Process

The Mayor and the Council should be enabled by a process that allows them to work together collaboratively and facilitates direct negotiations between the Mayor and Council leadership. This would be a more achievable goal if the Council were more independent, better staffed, and had a source of independent budgetary analysis. Below, we lay out the specific changes that City Council could make to enhance its authority and participation as the fiduciary over the Chicago budget.

Information Control and Leadership Structure

The Illinois Municipal Code designates the Mayor as the presiding officer of the Council, but the Council Rules of Order currently allow the Mayor to appoint committee chairs, including the budget and finance committee. There is no clear leadership within the Council. The Mayor dictates the City Council meeting schedule and agendas.

Establishing a leadership structure independent of the Mayor would empower the City Council by allowing it to select a leader from within its own ranks to oversee the appointment of committee chairs, set committee agendas, facilitate negotiations with the executive branch, and designate a formal negotiating team for budget matters.

In order to ensure that City Council has access to all information used in the creation of the Mayor’s proposed budget, the Council should also require the Mayor’s Office and all departments within the executive branch to share all information requested by the Council. This could come in the form of a municipal ordinance creating a mandatory duty to share information when requested by the Council and cooperate with all hearings held by Council committees.

To strengthen the Council’s role in the budget process, alderpersons should revise the Council’s Rules of Order to:

- Elect a “Speaker” or similar leadership position who would be responsible for managing committees and committee chairs, facilitating communication between the Council and the Mayor, and helping identify a budget negotiating team.

- Allow the Speaker to nominate committee chairs for the Council’s approval without executive influence.

- Require the Speaker to select a budget negotiating group charged with collecting feedback on the budget from all of Council and negotiating with the Mayor on behalf of a majority of alders.

- Legislate a duty to share all information and analysis relevant to the budget with Council, and a requirement for department heads to appear when summoned to testify at Council or committee meetings.

Resources

City Council’s limited capacity to analyze and respond to the Mayor’s budget reflects both constrained funding and the structure and use of existing staff, including the small side of the Council Office of Financial Analysis (COFA) and the lack of professionalized committee staff.

COFA serves as Chicago’s primary independent legislative budget analysis office, yet it lacks staffing, funding, and institutional independence typical of peer-city models such as the IBO in New York. New York City’s Charter specifies a budget floor for the IBO of 10% of the Mayor’s budget office expenses. This puts the IBO’s budget currently at an annual budget of $7.8 million with 40 staff. COFA’s 2025 budget was $529,075 with five budgeted positions. Had COFA’s budget represented 10% of OBM’s budget, it would have been closer to $1.8 million. The City Council should consider how it can better empower COFA or its eventual replacement through more staffing and more professionalized staff with specific expertise. The City should consider setting a budget floor to ensure it has enough resources to perform its duties. To be effective, the office must be professionalized, insulated from patronage, and given a clear mission and authority to support Council-wide budget review and negotiations.

Improving committee staffing will require a two-part solution. First, City Council must clearly separate committee work from ward-based constituent service. Committee staff and ward staff serve different roles and should not be conflated; this is specified under existing state and municipal law and regulation. Committee staff, especially those of the budget and finance committees, must focus exclusively on supporting committee operations and building subject-matter expertise. They should not be diverted to ward-level constituent service or other political work for committee chairs. These changes will require power shifting within the Council, which only makes the designation of an internal Council leader more important to enforce the proper usage of committee staff.

Second, the Council must professionalize committee staff and direct their focus on supporting the committee rather than ward-based services or other political work. This means hiring subject-matter experts to staff committees and developing the policymaking expertise of newer staff. Committee staff should not be hired on a political basis, as is the case for ward staff, but rather on a basis of merit and expertise. Budget Committee staff ought to be budget experts who are capable of crafting amendments or alternatives to the Mayor’s proposal, and they should serve all committee members, not just the Chair. To facilitate this professionalization, the Council should also seek to hire an administrative officer tasked with overseeing the human resources management of Committee staff.

In summary, there are two key ways City Council could improve its resources to make it a more empowered and independent branch of government:

- Substantially strengthen COFA, with an eye towards tripling the size of its budget and staff. It should also ensure that staff bring the right mix of subject-matter expertise in public finance, revenue forecasting, and debt and pension analysis.

- Professionalize committee staff:

- Require that committee staff be focused on the work of their committee rather than constituent service or other tasks benefiting only the chair.

- Reformat hiring guidelines for committee staff to focus on skills and expertise relevant to the committee’s work.

- Hire an administrative officer tasked with managing the Committee staff's human resources.

While these staffing changes would incur a small upfront cost to the City, the return on investment in good government outweighs the cost of continued poor financial decision-making.

Timing

While longstanding practice has the Mayor deliver a proposed budget in mid-October, this schedule has developed as a convention over time (and complies with the Illinois Municipal Code requirement for budget introduction by November 15). The current customary mid-October budget release leaves the Council with insufficient time to conduct meaningful review, develop alternatives, and negotiate changes before final adoption. An earlier submission would provide the Council with more time to evaluate, amend, and pass the budget, reducing the time pressure that has contributed to rubber-stamping and, more recently, conflicts between the executive and legislative branches. Establishing a longer budget timeline with clear and enforceable milestones would improve transparency, strengthen legislative oversight, and move Chicago toward a more balanced and collaborative budget process comparable to other large cities.

The Chicago City Council should revise its procedural rules to require the Mayor to submit a proposed budget earlier in the year. Submission by September 1, for example, would allow a four-month runway to pass a budget by the December 31 deadline. As part of the timeline shift, the Council should also establish a requirement that it produce a formal response to the Mayor’s budget partway through the cycle, such as by early November. This would compel both branches to clearly articulate their fiscal priorities and create a defined window for negotiation well in advance of year-end deadlines.

As part of this adjustment to an earlier budget introduction, other reporting and financial oversight activities should shift to earlier in the year as well. Amendments to the City’s management ordinance in 2024 resulted in mid-year hearings held in 2025, but they were scheduled for September, too late to be useful. The City’s mid-year budget forecast should be released at the mid-year point annually by July, accompanied by earlier hearings where Council members hear testimony from department heads about year-end projections and flag issues that could impact the next year’s budget.

The City Council should redefine the timeline of the budget process and consider the following specific changes:

- Require the Mayor to introduce a budget proposal earlier than October (for example, by September 1).

- Move mid-year hearings and other year-round oversight to earlier in the calendar year to allow for a lengthened budget timeline and more time for alders to prepare ahead of the budget introduction.

- Require the Council to provide a formal response to the Mayor’s proposal, outlining amendments and possible alternatives to the Mayor’s plan. This could be facilitated by a chief budgeteer and designated team of alders selected by City Council.

Securing Budget Process Reform through a City Charter

The major reforms to the budget process laid out above can and should be executed immediately by the Council. But these would best be enacted as part of an enforceable framework of reforms to the City’s broader governance structure. Chicago’s governance practices are based on anachronistic institutional norms rather than being codified in law or ordinance. Many of the City’s processes are holdover structures from the past. For example, alders often act as ‘mini-mayors’ within their wards, dictating everything from zoning regulations to the filling of potholes. Although some of this power has been centralized in recent years, the structure and powers of City Council still incentivize alders to focus primarily on their roles as curators of their wards rather than as legislators for the entire City. To change not just policy, but also culture, requires a total restructuring of the Council itself, as well as its relationship with the executive branch of City government. Thus, the argument for a city charter.

Chicago is the only major U.S. city that does not have a charter—a city constitution that formally defines the roles, powers, and responsibilities of government. A city charter could reimagine the Council by providing it with the power to negotiate on even footing with the Mayor. Other city charters, such as that of New York City, empower their Councils by establishing guardrails for appointments of committee chairs, staffing, and access to independent information and analysis. At the same time, they centralize region-focused powers like those currently wielded by Chicago alders by moving them to the executive branch, incentivizing Council members to act as legislators and as checks on the Mayor rather than focusing on the minute issues of their own wards.

Chicago is an outlier among all major cities in America in many ways. One of the largest examples is the territoriality of its government. If alders were incentivized to pay more attention to the City as a whole than to their own fiefdoms, Chicago would benefit from a much more robust and assertive legislative branch. A charter could both force and empower the Council to look at the forest rather than the trees.

Risks of Inaction

Chicago’s current budget system is failing us. The most recent City budget does not meaningfully address the billion-dollar structural deficit the City faces and avoids many of its most difficult financial challenges. Instead, it increases an already heavy debt burden, makes only marginal progress on streamlining City government, and places the costs of adjustment largely on taxpayers rather than sharing them across stakeholders.

One way or another, Chicago will have to face its fiscal problems head-on. The changes in this budget are unlikely to be sufficient to prevent the credit downgrade warned of by S&P, and investors have made it clear that they are concerned about Chicago’s risk profile as a debt issuer. If the City continues to collect debt and pension obligations like a snowball rolling down a hill, it will eventually hit a point where it has no choice but to cut essential services or default on its legal obligations. It is hard to say exactly when Chicago will reach a fiscal cliff, but we are much closer today than we were a month ago. If Chicago crosses the dangerously close line into a junk credit rating, the City may find itself at a crisis point. If we are to avert that crisis, we must have a Council that is responsible and empowered. The 2025 budget chaos showed us that we now have the first, but it also showed that a responsible council is not enough to truly solve our problems without the structure and support necessary to check the Mayor's power.

Council members should take notice. They must act as true co-stewards of the City’s finances, equip themselves with the tools necessary to govern effectively, and reform the budget process as soon as possible—2027 is just around the corner.