January 26, 2026

by Grant McClintock and Daniel Vesecky

The final FY2026 City of Chicago budget, passed by City Council on December 20, brought a conclusion to an unprecedented and complex budget season. The result, which took effect January 1 without a signature or veto from the Mayor, should leave Chicagoans expecting much better of the City Council and Mayor alike. The unprecedented City Council-generated alternative FY2026 budget, while a valiant attempt to flex muscles the Council has always theoretically had but never used, represents another year of budgeting on the margins while leaving unaddressed the City’s mounting structural deficit, which will only continue to present challenges in the years to come.

While the Council’s version of the adopted budget improved somewhat on the Mayor’s initial proposal, it still falls far short of what is needed to address Chicago’s deeply challenged financial situation. Among other things, the Council budget wisely makes Chicago’s full advance pension payment. But it still relies on a shocking amount of new borrowing for operating costs, as well as an unprecedented TIF surplus sweep, which could impair economic development capacities and will not be sustainable in the future. The final budget includes some of the very things that credit rating agencies warned would trigger new downgrades and, with them, higher debt service costs.

Neither the Mayor’s budget proposal nor the version passed by City Council reflects the necessary burden-sharing among all stakeholders. Instead, the budget relies heavily on taxpayers, both individual and corporate. The budget also leaves out significant opportunities for savings and efficiencies—falling short on cost-cutting and leaving labor completely off the hook for sharing the burden of balancing the budget, in a city government in which personnel expenses and benefits account for 70% of the operating budget. While the City’s finances have not yet reached the point of a full financial crisis, the FY2026 budget continues on the downward path with no clear plan to reverse course.

Highlights and Lowlights From the Adopted Budget

The Chicago City Council closed a projected $1.2 billion budget gap by adopting a $16.6 billion budget for FY2026 in late December, rejecting the budget the Mayor had proposed in October. The budget falls short in the following ways:

- Includes only a handful of efficiencies and cost savings.

- Uses debt, rather than operating revenue, to cover the cost of legal police settlements and retroactive salaries for firefighters.

- Puts the burden entirely on taxpayers while exempting labor from any shared burden.

A welcome change in the Council’s adopted budget from the Mayor’s proposed budget is the addition of the City’s full advance payment to the pension funds. The Mayor’s proposal cut the advance payment from $238.6 million to $120.2 million to free up funds to close the budget gap. However, this prompted S&P Global Ratings to revise its outlook on the City of Chicago's debt from stable to negative, signaling potential future rating downgrades. The advance (or supplemental) pension payments the City began making in FY2023 have helped stem the growth of unfunded pension liabilities, although fiscally reckless legislation passed in Springfield last year greatly increased the City’s pension exposure through a sweetener to the already grossly underfunded police and fire pension funds. The adopted budget includes the full supplemental contribution.

But despite making the full advance pension payment, the alternative budget continues mistakes of the past that have led to the gradual worsening of the City’s structural deficit—namely borrowing for operations while doing the bare minimum to curtail spending. This is likely to hurt the City’s credit rating.

Already flush with borrowing authority, City Hall authorized even more as part of the FY2026 budget package through a $1.8 billion authorization to issue new debt. This included about $450 million in debt to pay for non-capital operating costs: $166 million to cover back pay for firefighters under a recently approved collective bargaining agreement, and $283 million to cover the cost of police misconduct settlements. The remainder of the authorization will purportedly be used to fund capital and infrastructure projects and refinance up to $1 billion in existing debt. Some of this borrowing might possibly have been avoided if the City had not stripped the TIF pantry bare with this budget.

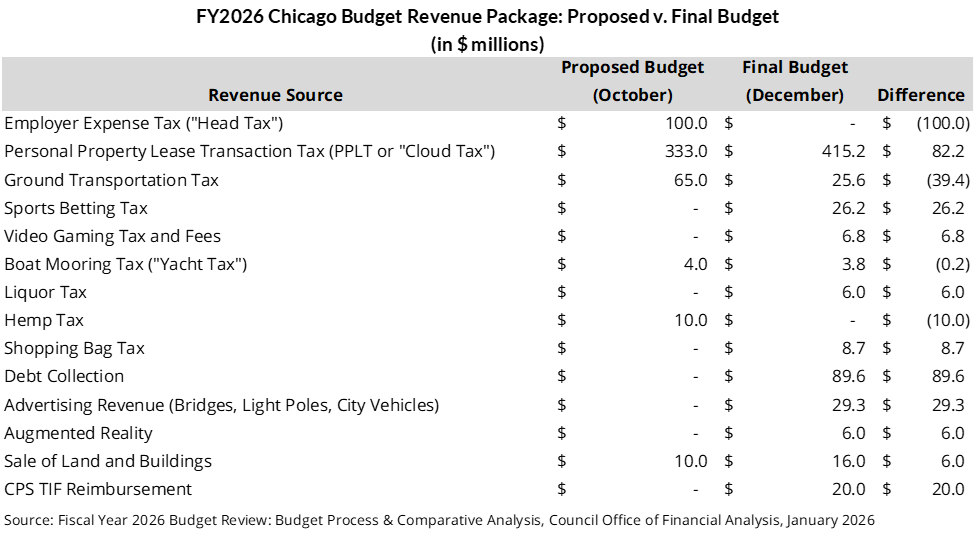

The adopted budget makes several other significant changes from the proposed budget, including the elimination of a per-employee head tax estimated to generate $100 million and an increase in the personal property lease transaction tax (“cloud tax”) to 15%. This will raise the cloud tax rate by another percentage point, from the Mayor’s proposed 14% to 15%, and by 4 percentage points from the prior rate of 11%, to generate a total of $415 million in new revenue. Some other tax sources were added or increased as part of the final budget revenue package. These changes from the originally proposed budget are shown in the table below.

The final revenue package notably still includes a Tax Increment Financing (TIF) surplus distribution to the City of $232.6 million. This represents slightly less than a quarter of the City of Chicago's $1 billion TIF surplus (Chicago receives approximately 23%, while the remainder is distributed to other Chicago-based taxing agencies under state law). Over $500 million in TIF surplus was distributed to the Chicago Public Schools (CPS), of which $175 million was returned to the City as a reimbursement for the City’s payment into the Municipal Employees Benefit and Annuity Fund (MEABF), a pension fund which covers some CPS employees. This $175 million was used to close the gap that had emerged in the City’s FY2025 budget, and the remaining $20 million was directed toward the FY2026 deficit.

The 2026 TIF surplus is the largest ever declared by the City. However, while TIF surpluses have been increasing steadily in recent years, the City will not be able to count on these levels in future years as many TIF districts are set to expire within the next ten years. It should also be noted that TIF funding is designed and intended to be used as an economic development tool, not a general operating revenue source.

No Attempts at Meaningful Cost Reductions

Noticeably absent from the final budget are material measures to reduce structural spending year over year. The final budget maintains the Mayor’s proposal efficiencies, of which less than $20 million are structural initiatives to improve procurement processes, modernize fleet management, recover the cost of special events, in addition to one-time revenue bumps from a hiring freeze to save $50 million and about $12 million in revenue from consolidating the City’s real estate footprint and selling unused buildings.

The City Council’s alternative budget added an additional $46.6 million in efficiencies, although decisions on what efficiencies and cost reductions to pursue are left up to the Mayor and the Office of Budget and Management.

A report produced by the consulting firm EY (formerly Ernst & Young) in October outlined a wide-ranging suite of possible annual expenditure reductions and savings the City could pursue beginning in FY2026, which, over time, could yield an estimated $530 million to $1.4 billion in savings. While not all of these savings could be implemented immediately or realized in the coming budget year, both the proposed and adopted versions of the budget omitted many potential efficiencies, such as optimizing fleet service staffing, renegotiating employee benefits, and implementing category management for consolidated citywide procurement. There is much more work that could and should, given the City’s fiscal situation, be started now to reduce costs related to fleet services, employee benefits, organizational structure, and public safety service optimization—all areas where EY founds tens of millions of potential savings. Additionally, the budget has little to say on the question of the long-term work needed to implement many of EY’s larger proposals, such as procurement reform, optimization of the City’s management structure, and civilianization of the Chicago Police Department, all of which the Civic Federation endorses for further examination and planned implementation. Ultimately, this budget missed an important opportunity to begin to meaningfully address the City’s structural budget deficit by reducing costs.

In addition to minimal efficiencies, the adopted budget avoided asking labor partners to share in the burden of cutting expenditures at a time when revenues are not growing enough to keep pace. This could have come in the form of furlough days—an immediate, but not long-term solution—or beginning the hard work of conducting a full analysis of personnel to determine which positions (filled or unfilled) across each department are needed. The City needs to address the misalignment between its current personnel and vacancies and what it actually needs. Although the budget proposal saves money by enacting a hiring freeze, such a move is not a long-term efficiency, as the City must eventually resume hiring. In addition, multiple consecutive hiring freezes leave a growing number of vacant positions open for years, likely resulting in further inefficiency throughout City government.

Ongoing Structural Issues

Chicago’s FY2026 budget will allow the city to eke out another year, but ultimately leaves the City in the same place in the next FY2027 budget cycle unless serious work is done this year to address the City’s structural problems.

Chicago has an ongoing structural deficit. This means recurring expenses consistently grow faster than sustained revenues, creating a long-term imbalance and often leading to the use of one-time funds to plug gaps (e.g., federal ARPA funding or short-term debt). This is a fundamental mismatch in which spending rises beyond normal revenue collection year after year, highlighting the need for deep spending cuts or new revenue sources.

Sequential budget deficits have led to a customary practice of short-sighted financial decision-making, such as using one-time or unsustainable revenues to plug budget holes. Much of the increased spending and resulting budget deficits are driven by the fact that 40% of the City’s total budget is consumed by legacy costs of pension contributions and debt service payments, which crowd out the ability to fund discretionary services. The failure to meaningfully address the structural deficit spiral could lead to further credit ratings downgrades, which will increase the cost of borrowing and continue to exacerbate the City’s financial problems.

The backdrop to these concerning realities is an economic situation in which the City is experiencing stagnant job growth, a housing shortage, rising cost of living, and a perception of being unfriendly to business. All of these issues are disincentives to growth and raise concerns that revenue streams may decrease over time.

Spending Increases

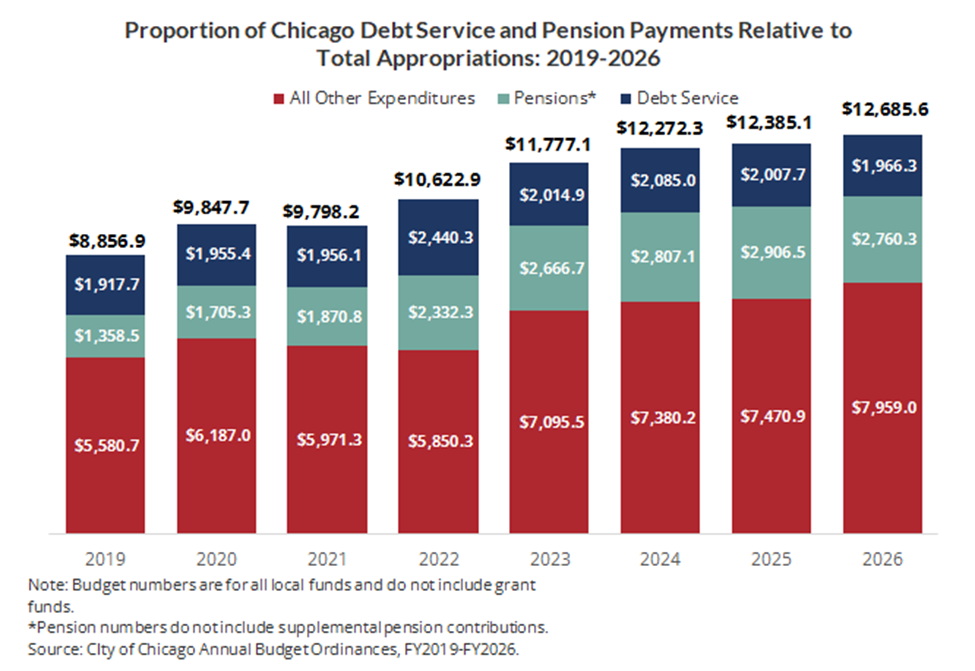

Because the City has left its structural deficit unaddressed, spending continues to grow year over year without sufficient, sustainable revenues to cover rising costs. As the Civic Federation noted in an October report, Chicago’s budget has increased 40% since 2019, excluding grant funds. Much of this growth is attributed to legacy costs—pension contributions and annual debt service expenditures—that are fixed and therefore non-discretionary. The largest driver of the spending increase, pensions, accounted for a $1.5 billion increase over the six-year period, driven by rising obligations and supplemental payments. Many of these increases were mandated by the State and are needed to keep the City compliant with the State-imposed funding schedule.[1]

Debt service payments on principal and interest for long-term borrowing also make up a significant portion of the City’s spending. However, this has recently become a lower proportion of total expenditures. Combined, these two mandatory funding obligations comprise 40% of the City’s operating budget and therefore crowd out spending on other government services. The table below shows the spending for each over the past eight years, using 2019 pre-COVID as the baseline.

In addition to fixed legacy costs associated with paying down pensions and long-term debt, departmental spending has also increased over time. All other City spending increased by about 50% between 2019 and 2026.

Additionally, there will be more financial pressures in the upcoming years. These include a State-imposed pension sweetener for the City’s police and fire funds that adds billions in unfunded liabilities—setting the stage for even higher pension contributions going forward. Further, the City’s issuance of $830 million in backloaded debt in February and another $1.8 billion in bonding authority approved as part of the FY2026 budget to cover operational costs in addition to infrastructure costs will also demand increased tax dollars for debt service. Without sufficient revenue to support large spending increases and without a meaningful attempt to reduce expenses, marginal increases in taxes and fees each year will become unsustainable as obligations continue to grow.

Pension Crisis

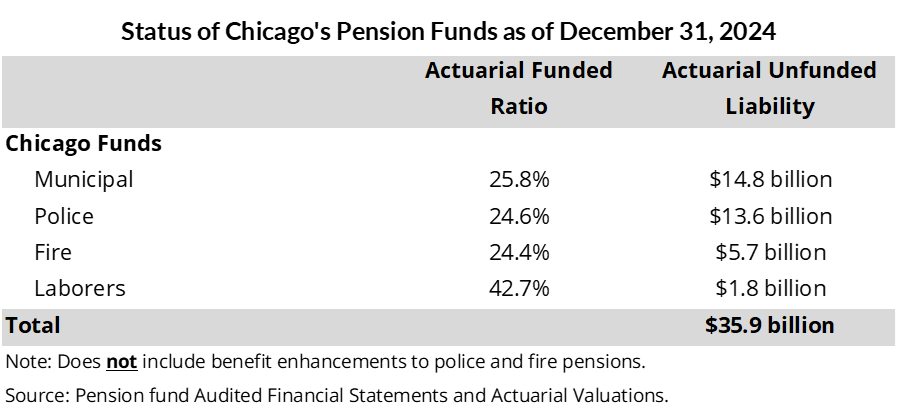

Despite the City continuing to put more money into the pension funds each year, Chicago’s four pension funds remain among the most poorly funded in the nation and are on the verge of evolving into a full-blown crisis for the City. As the table below shows, Chicago had a combined $35.6 billion in unfunded pension liabilities, with two of four funds below 25% funded, as of the most recent actuarial valuation reports (2024). This severe underfunding derives from generations of poor decisions at multiple levels of government, including statutory underfunding, benefit enhancements, investment losses, optimistic assumptions, and other long-term problems. And because this crisis falls at the feet of multiple levels of government, each must collaborate to determine a solution before the pension crisis becomes the City’s financial crisis.

The funding situation has grown even worse following the passage of a bill (HB3657) in the spring 2025 legislative session that boosts pension benefits for Tier 2 Chicago police officers and firefighters (those hired since 2011). In July, the Governor signed legislation increasing benefits for Chicago police and firefighters in an attempt to ensure that retirement benefits meet the requirements of Social Security Safe Harbor and to bring parity with downstate first responders under Tier 2 pension plans. However, this pension sweetener threatens to push the City’s funds into insolvency. The cost of the added benefits is estimated to exceed $11 billion and add to the City’s unfunded liabilities over the next 30 years, and the funded ratio of the two funds has now dropped below 18%.

The police and fire pension funds will require an additional $60 million in employer pension payments from the City in FY2027, increasing gradually over the course of the 30-year funding schedule and totaling nearly $7 billion. Without significant revenue increases, it’s hard to see how the City will continue to manage the rising pension contributions that crowd out funding for other programs and services. The Chicago casino was supposed to serve as a major funding source for the police and fire pension funds. However, the temporary casino has significantly underperformed expectations, raising barely 44% of the originally projected revenue in 2025, and the permanent casino has experienced a series of delays that appear to push off operations for as much as another year beyond the FY2026 target. It is therefore highly unlikely that the $44 million in casino revenue projected for FY2026 will come even close to fruition.

While the four Chicago pension funds will eventually need benefit alterations to comply with federal Safe Harbor rules, the police and fire legislation overshot the benefit expansions needed to comply with this Social Security regulation. Another issue set to emerge is that the other two City pension funds—those for municipal employees and laborers—still need to address Safe Harbor compliance For the sake of doing no further unnecessary harm to the City’s financial situation, if the State seeks to make changes to these funds, it should make only the minimum changes required to keep them in compliance with federal regulations.

The pension funding crisis has not yet evolved into a financial crisis, but the City could be heading in that direction if the funds run out of assets and encounter cash-flow issues that impede their ability to pay out benefits to retirees.

Possible Credit Downgrade

All the factors discussed above point to the City heading for a possible credit rating downgrade. This should concern city taxpayers because lower credit ratings equate to higher borrowing costs, which in turn mean more funding must be dedicated to paying down debt—either by increasing revenue (taxes) or by cutting back in another spending area. Past City estimates indicate that every credit rating upgrade represents $100 million in long-term interest cost savings for each $1 billion in bonds issued. Every downgrade would therefore have the opposite effect.

For the past year, credit agencies have been sounding the alarm on Chicago’s fiscal practices, and the FY2026 budget does little to assuage their concerns. Following the passage of the FY2025 budget, several rating agencies issued credit downgrades for the City, largely based on persistently imbalanced budgets, woefully underfunded pensions, and high long-term debt burdens. The release of the proposed FY2026 budget in October prompted S&P to adjust its outlook on City debt from stable to negative, citing the City’s structural deficit and reduced supplemental pension payment, and warning of a further downgrade if structural adjustments are not made.

Despite slight improvements from the initial budget, this year’s budget does not address all of the rating agencies’ concerns about structural issues—i.e., having sufficient revenues to cover expenditures and avoiding the use of one-time measures to fill budget holes. The City’s general obligation bonds are currently rated at one notch above non-investment grade (“junk” status) by Moody’s, and two notches above junk by S&P. Fitch and Kroll assign higher ratings. If the City receives multiple credit downgrades that push its ratings below junk status, this would not only cost the City more to issue long-term debt but also could threaten access to credit markets and limit the pool of lenders willing to buy the City’s debt. This would result in rapidly rising interest rates on future debt issuances for Chicago, making it much more difficult for the City to maintain its spending on infrastructure needs. The City’s inability to sell $75 million in bonds in November indicates that markets may already be internalizing the expectation of such a downgrade.

Where does this leave us?

The most disappointing thing about this year’s budget is that it leaves the City in much the same place as where it started and threatens to undo progress made in recent years on the City’s credit rating and pension funding.

For the second year in a row, Chicago City Council increased its involvement in the budget process and, despite lacking resources and access to data, managed to develop an alternative budget that offered marginal improvements from the original. Still, the alternative budget falls far short of what is needed to strengthen the City's financial footing. It continues many of the practices repeatedly derided by credit agencies, misses critical opportunities for expense reductions and increased efficiencies, does little to promote economic growth, includes borrowing for operations, and relies heavily on revenue increases from an already burdened tax base with no meaningful sacrifice from labor.

Little attention was paid to the serious operational changes that could save the City tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. Crucially, neither the budget nor the Mayor’s Office provided any indication that the work needed to implement long-term efficiencies, such as procurement reform, had begun. Many of the changes needed to save the City money will take time. If the work does not begin now, the City will be in the same position in its next budget cycle – looking at a list of efficiencies that it has not started working on and does not have enough time to implement. As it provides legislative oversight over the implementation of the 2026 budget, City Council ought to pay special attention to demanding the implementation of the required efficiencies, as well as ensuring that the City is well-positioned to begin implementing some of EY’s larger recommendations in 2027.

The City Council’s break from rubber-stamping the Mayor’s budget for the second year in a row is a welcome check and balance. But the way the Council’s alternative budget played out points to growing political dysfunction, which was itself a factor the last time the City’s credit dropped to junk status. There is a dire need for a more robust, clear process that empowers the City Council to serve as an equal partner in the budgeting process. Breakdowns in process and information sharing need to be addressed early in FY2026 to position the City and Council overall to make greater headway in meeting the challenges waiting in the next budget cycle. The Civic Federation will soon publish a companion piece analyzing the now-concluded FY2026 budget process to make specific recommendations for measures that could and should be implemented by the end of the first quarter of FY2026. In the meantime, City Council and the Mayor’s Administration need to work together to begin addressing the City’s structural fiscal challenges now.

Read more of the Civic Federation’s related work on the Chicago 2026 Budget:

Chicago's FY2026 Proposed Budget: A Stumbling Start

Which Cuts Didn't Make the Cut - Efficiency Opportunities for Chicago's FY2026 Budget

Understanding Chicago’s 2026 Record TIF Surplus

Statement on City of Chicago FY2026 Budget

[1] See Council Office of Financial Analysis, “Understanding Chicago’s Pension System,” November 24, 2025.