August 08, 2012

(Click here to read part one of this two-part look at the City's Annual Financial Analysis.)

Last week, the City of Chicago released its Annual Financial Analysis for 2012. According to an executive order issued by Mayor Emanuel on May 20, 2011, the Office of Budget and Management is mandated to produce a financial analysis of the City budget by July 31 of each year. The analysis includes:

• A financial condition analysis that covers the previous ten years including a discussion of key factors impacting the performance of the City’s revenue streams;

• A three-year baseline forecast that describes key assumptions as well as alternative forecasts to show positive and negative variances;

• A reserve analysis that includes the corporate fund reserve and asset lease reserves;

• An analysis of the City’s capital improvement program; and

• An analysis of general debt obligations and long-term liabilities, including pensions.

The analysis includes year-end estimates for FY2012. The City’s fiscal year runs from January 1 to December 31; therefore, year-end estimates are based upon the first six months of the fiscal year.

In last week’s blog, the Civic Federation described key facts about the City’s Corporate Fund and projected budget deficit for FY2013 as reported in the Annual Financial Analysis. Today’s blog post will address the City’s future budget stressors included in the 2012 Annual Financial Analysis – pension liabilities and long-term debt.

Pension Liabilities

According to State of Illinois Public Act 96-1495, the City must fund its Police and Fire Pension Funds at the actuarially-determined level that is sufficient to bring their funded ratios to 90% by the end of 2040. According to actuarial value of assets, at the end of FY2011, the City of Chicago’s four pension funds were at the following levels of funding:[1]

· Municipal Employees’ Annuity and Benefit Fund – 41%;

· Laborers’ and Retirement Board Employees’ Annuity and Benefit Fund – 61%;

· Firemen’s Annuity and Benefit Fund – 26%; and

· Policemen’s Annuity and Benefit Fund – 33%.[2]

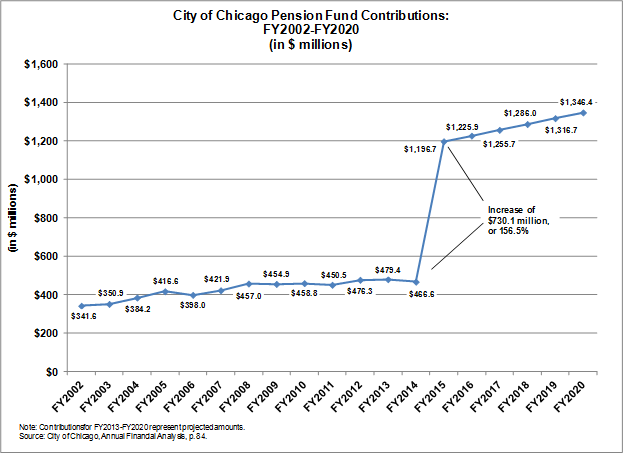

The funding change will cause contributions to the Police and Fire Pension Funds to rise from $476 million in FY2012 to $1.2 billion in FY2015 and then increase to $1.35 billion in 2020.

The chart below depicts the City’s previous and projected future contributions to its four pension funds. In comparison, the City’s current property tax levy, the primary funding source for pension payments, is $797 million.[3]

Addressing this issue will require some combination of the following: huge increases in the property tax levy, significant cuts to City services and substantial reductions in pension benefits. In May 2012, Mayor Emanuel proposed a plan for significant pension reform for employees of the City of Chicago, Chicago Public Schools and Chicago Park District during a hearing of the Illinois House of Representatives Personnel and Pensions Committee. The proposed reforms would reduce the City’s $20 billion unfunded liability for the City’s four pension funds, the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund and the Park District Pension Fund by 40%. Click here to read more about the Mayor’s proposal.

For more information on the City of Chicago’s pension funds, see the Civic Federation’s “Status of Local Pension Funding: FY2010.”

Long-Term Debt

The City of Chicago proposes a five-year (2012-2016) capital improvement program of $7.7 billion. The program includes more than $3 billion in water and sewer improvements. The remaining amount will be designated to infrastructure ($2.2 billion), aviation ($2.2 billion), greening of the City ($136.4 million) and facilities improvements ($92.0 million).

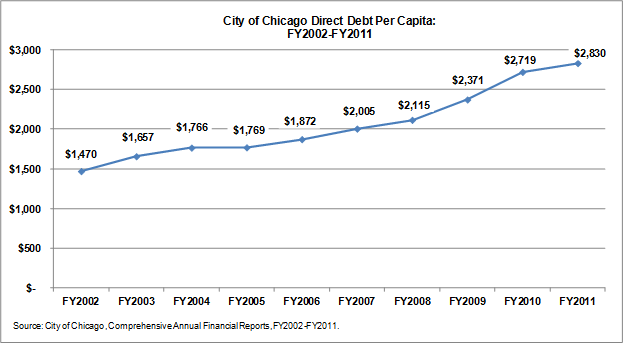

The City of Chicago’s budgeted debt service appropriations for FY2012 were projected to be $1.4 billion, which is 22.9% of budgeted appropriations totaling nearly $6.3 billion. Credit rating agencies take into account a government’s debt load when assessing that government’s bond rating. They regard debt service that exceeds 20% of operating revenues as a potential problem; 10% and below is considered acceptable.[4]

Between FY2007 and FY2011, direct tax supported debt per capita rose by 41.2% from $2,005 to $2,830. This upward trend comes amidst a ten-year increase in the City’s direct debt per capita of 92.5%, which is a per capita increase of approximately $1,360. This sharp upward trend in direct debt per capita between FY2002 and FY2011 is cause for concern for the City of Chicago. It threatens to further reduce the City’s credit rating, making borrowing more expensive and possibly limiting available capacity for additional borrowing.

[1] Actuarial value of assets: Under Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB) Statement No. 25, assets of public pension plans may be reported based on their actuarial, or smoothed, value. The actuarial value typically smoothes the effects of short-term market volatility by recognizing deviations from expected returns over a period of three to five years. For example, one smoothing technique recognizes 20% of the difference between the expected (based on the assumed rate of return) and actual investment returns for each of the previous five years.

[2] City of Chicago, Annual Financial Analysis 2012, p. 82.[3] City of Chicago, Annual Financial Analysis 2012, p. 83.

[4] Craig S. Maher and Karl Nollenberger, “Revisiting Kenneth Brown’s “10-Point Test,” Government Finance Review, October 2009. See also Standard & Poor’s, “U.S. State Ratings Methodology,” January 3, 2011.