January 03, 2014

States inevitably face lawsuits when they attempt to ease budgetary pressures by cutting pension payments to current employees and retirees. While the legal battle over Illinois’ new pension law has just begun, courts have already issued rulings on similar pension changes in other states.

Like Illinois, other states have enacted pension laws that rely on savings from reductions in annual benefit increases. Court decisions on whether states have the ability to reduce these cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) have varied widely, making it difficult to predict whether COLA reduction is a viable option for states seeking to shed pension obligations, according to Amy Monahan, a pension law expert at the University of Minnesota.

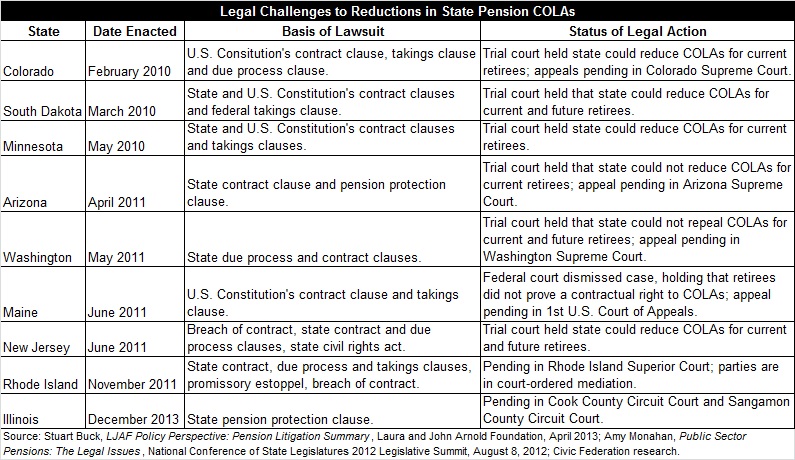

The following table provides a summary of state cases related to pension COLA reductions for current employees and retirees. The table is based partly on a report by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, which promotes alternatives to traditional defined benefit pension plans for public employees.

The legal protection available to state employee retirement benefits depends on state law. It is important to understand that court decisions in one state are not binding on other states and that even legal experts cannot predict the decisions of Illinois’ elected Supreme Court.

In the early 1900s, state courts considered pensions to be gratuities from the government that could be changed or repealed at any time. This legal approach changed over time in most states to provide more protection to employees. Most pension benefits are now covered by contract or property rights theories that generally protect previously accrued benefits. The protection of benefits that are not yet accrued varies significantly by state. In general, this means that legal protections are strongest for current retirees. Even for current retirees, however, some courts have provided lesser levels of protection for COLAs.

Illinois is considered to have among the most stringent pension protections. It is one of a handful of states, including New York and Arizona, with specific constitutional provisions barring benefit reductions.

The Illinois Constitution of 1970 (Article XIII, Section 5) states: “Membership in any pension or retirement system of the State, any unit of local government or school district, or any agency or instrumentality thereof, shall be an enforceable contractual relationship, the benefits of which shall not be diminished or impaired.” An account of the origins of Illinois’ constitutional pension clause by Eric Madiar, chief legal counsel to Illinois Senate President John Cullerton, can be found here.

A lawsuit filed on December 27, 2013 in Cook County Circuit Court by the Illinois Retired Teachers Association maintains that Illinois’ new pension law violates the pension protection clause by limiting COLAs paid to retirees, among other changes. The new law, which is scheduled to take effect on June 1, 2014, also requires that current employees forfeit as many as five COLAs when they retire.

A second lawsuit challenging the reduction of annual benefit increases was filed in Sangamon County on January 2, 2014 by the Retired State Employees Association. This lawsuit also alleges violations of the Illinois pension protection clause.

Under existing Illinois pension law, current retirees and employees hired before 2011, upon retirement, receive an automatic annual 3% compounded increase in their benefits. Regardless of the rate of inflation, the 3% increase is applied to the initial benefit amount plus previously earned increases. Benefit reductions passed in 2010 for employees hired on or after January 1, 2011 eliminated compounding and reduced annual increases to 3% or half of the increase in the Consumer Price Index, whichever is less.

In 2011 Arizona, a state with constitutional pension protections similar to those in Illinois, enacted a law that limited COLAs for retirees and current employees. A judge in the Superior Court of Arizona, Maricopa County, ruled in May 2012 that the change unconstitutionally impaired benefits that had been earned by retirees. The decision has been appealed to the Arizona Supreme Court. The state was also ordered to transfer funds into a reserve for future benefit increases and to pay retirement benefits based on the previous law.

Most states do not have explicit constitutional guarantees of pension benefits, but courts have determined that contractual protections exist based on statutory language or employment relationships.

In the State of Washington, for example, the Superior Court for Thurston County in November 2012 ruled that the State could not repeal automatic COLAs. Employees have a vested right to COLAs because they began work partly on the promise of a COLA and the State offered no offsetting benefit, the court ruled. The ruling has been appealed to the Washington Supreme Court.

If a contract is found to exist, a change still may be constitutionally permissible under a two-step test promulgated by the U.S. Supreme Court: 1) Has the contract been substantially impaired; and 2) Even if it has been substantially impaired, is the impairment reasonable and necessary to satisfy an important public purpose.

Rhode Island’s pension reform law enacted in 2011 suspended COLAs until pension funding levels reached 80%. Retirees allege in a lawsuit that they have a contractual right to pension benefits, including COLAs, that starts at the latest when they become eligible for retirement. The retirees also argue that their benefits will be substantially diminished and that the State cannot prove that the law serves a reasonable and necessary public purpose. The case has been sent to mediation.

The Rhode Island Supreme Court, four days after the 2011 law was enacted, declined to review a ruling by a lower court on an earlier round of pension reforms that public employees had an implied contractual right to pension benefits. That ruling emphasized that the same legal analysis applies to COLAs as to base pension benefits.

A lower court in Colorado ruled in June 2011 that retirees had a contractual right to their pension but not to the specific COLA formula in place when they retired. An appellate court reversed the decision in 2012, ruling that retirees had a contractual right to some COLA provisions but that it must be determined whether any impairment was substantial and if so whether it served a significant public purpose. Both the state and retirees have appealed to the Colorado Supreme Court.

In Minnesota pension protections are based on promissory estoppel, a legal principle that implies a contract where none exists if harm results from reasonable reliance on a promise. The Second Judicial District Court in Ramsey County ruled in June 2011 that there was no evidence the legislature intended to create a contract with respect to specific COLA amounts; that in any case the COLA change was not substantial; and that even if it were substantial it was a reasonable exercise of legislative authority, designed to balance retirees’ interests and the need to stabilize the pension system.

Even states like Illinois with strong constitutional protections for pensions have some legal options for reform, according to experts. One possibility is for each employee to voluntarily agree to plan changes. A version of this approach has been supported by Senate President Cullerton, who has maintained that reducing pension benefits would be constitutional only if employees and retirees were given something of value in exchange. The new Illinois law includes a modest reduction in employee contributions, but it is not clear whether that would be valuable enough to offset other changes.

The Illinois law appears to rely mainly on a legal argument relating to the State’s police power, its inherent ability to take action necessary to preserve public security, order, health, morality and justice. However, the changes must meet the difficult legal standard of being reasonable and necessary to serve an important public purpose. The Illinois Supreme Court rejected the police power argument in a 1985 decision relating to the Judges’ Retirement System.

Illinois currently has the lowest credit rating of any state and the most underfunded retirement systems. The preamble to the new pension law describes the State’s financial problems and steps already taken to fix them. It concludes: “Having considered other alternatives that would not involve changes to the retirement systems, the General Assembly has determined that the fiscal problems facing the State and its retirement systems cannot be solved without making some changes to the structure of the retirement systems.”